How Memphis Neighborhoods Have Evolved

Neighborhoods can be a tricky thing to define, both geographically and socially. Where does one neighborhood start and the other end? Why are some neighborhoods demographically and culturally uniform while others are more varied? Typically, neighborhood residents share some common trait, such as a specific country of origin or socio-economic status. In the history of Memphis, race has been the commonality in most neighborhoods. Beyond broad common characteristics, each neighborhood also has its own reputations, values and boundaries. Let’s take a closer look at how neighborhoods in Memphis have evolved over the years.

In the Beginning

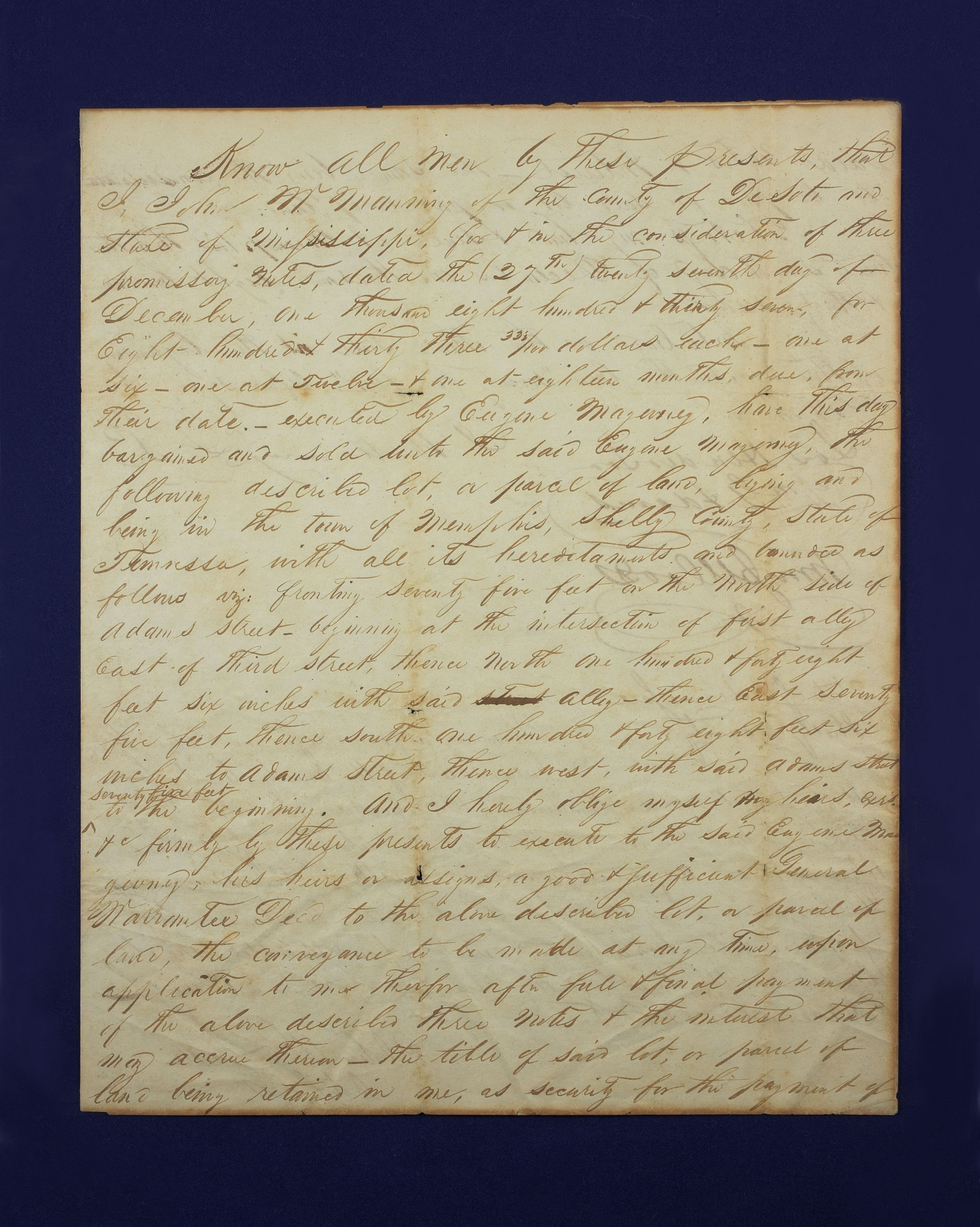

While the Lower Mississippi River frequently flooded most of the lands on its banks, Memphis’s position atop the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff made it much less vulnerable to flooding. This gave the city incredible potential as a center of trade and commerce in the region and the initial plans had to accommodate for the city’s inevitable growth. With this in mind, Memphis’s founders, Andrew Jackson, James Winchester, and John Overton, designed the city’s original layout. The plans featured much of what we know as Downtown Memphis today, including the Pinch District and Uptown to the north and the Central Business District surrounding Court Square to the south.

Memphis’s importance as a port town, first for river travel and later as part of America’s growing railroad system, led to rapid population growth in the first half of the 19th century. With the vast expanse of the Mighty Mississippi to the west and floodplains covering much of the land to the north and south, this left Memphis with just one direction for growth: East.

Trials and Tribulations

Memphis continued to grow during the mid-19th Century, becoming the sixth largest city in the South in 1860. The city was even lucky enough to emerge from the Civil War relatively unscathed compared to many other major Southern cities. And with the emancipation of enslaved peoples at the end of the Civil War, several African American neighborhoods began sprouting in South Memphis. Unfortunately, this promising development was cut short by a devastating, horrifying event.

In 1866, racial tensions resulted in three days of violence and bloodshed when white residents and policemen attacked the black community. By the end of this event, known as the Memphis Massacre of 1866, forty-six African Americans were murdered, many more injured and much of their newly established neighborhoods in South Memphis, including every school and church, destroyed. This led much of the black population to relocate to more rural locations outside of Memphis or leave the city entirely.

Revival, Expansion, and Segregation

Repeated Yellow Fever epidemics in the late 1800’s had dramatically reduced the population of Memphis to the point that the city lost its city charter for fourteen years. However, Memphians did not lay idle during this time. Local leaders revitalized the city by creating a new and much more sophisticated sanitation system. The Memphis Sands Aquifer was discovered beneath the city, guaranteeing a clean and bountiful water supply. And in 1892, the Frisco Bridge was completed, becoming the first bridge to cross the Lower Mississippi River. Memphis trade and commerce returned, and the city began to recover.

Building on this momentum, Memphis began expanding in earnest during the early 20th Century. There was an increased focus on city beautification, which included improving Memphis’s infrastructure and creating a system of public parks. In 1901, city leaders purchased land that would soon be the grounds for both Overton Park and Martin Luther King Jr. Riverside Park (originally named Riverside Park). To connect these parks to Downtown and to each other, George Kessler, a city planner, created what we now know as the Parkway System. The Parkway System refers to North Parkway, East Parkway, and South Parkway. Upon the System’s completion in 1906, the parkways served as the new general boundaries of Memphis. Many current Midtown neighborhoods, including Central Gardens, Binghampton, Evergreen and Cooper-Young were part of this freshly annexed land.

Since Jim Crow laws made racial segregation legal, the African American community experienced limited benefits from Memphis’s revival. So, while this eastward expansion drove the growth and creation of new white neighborhoods, black Memphians began carving out their own piece of South Memphis. Orange Mound became the first African American neighborhood in the nation to be built by and for African Americans. Orange Mound has thrived for nearly a century, becoming to Memphis what Harlem is to New York City – a center of African American culture with a strong middle-class community.

East Memphis and Poplar Plaza

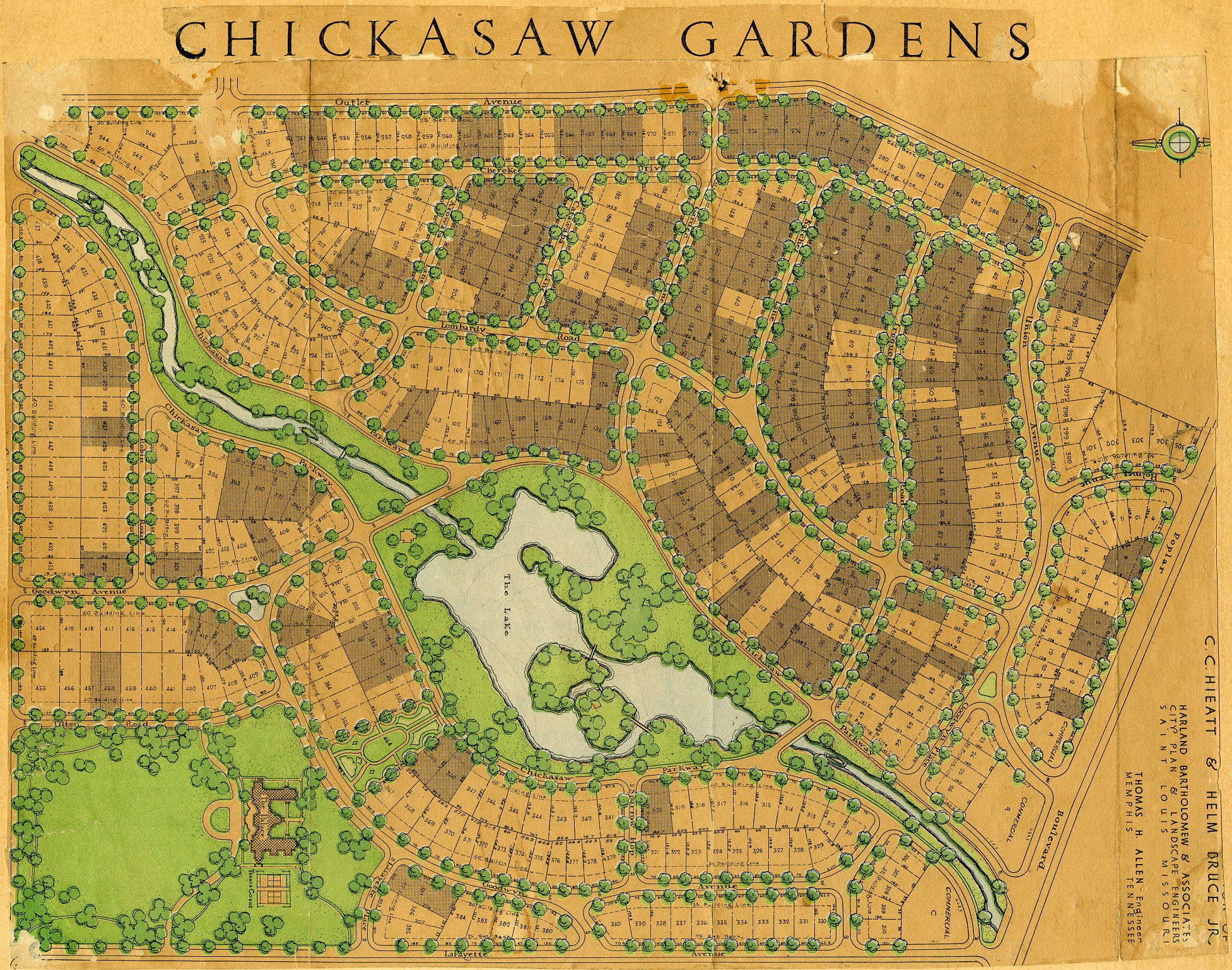

As the 20th century wore on, Memphis became a city increasingly dependent on automobile transportation. The majority of Memphians still worked Downtown but could commute longer distances thanks to the automobile. Expansion continued eastward, beyond East Parkway along Poplar Avenue and other major roads (collectively known as the Poplar corridor). Again, it was wealthier white families who made the initial move, creating the neighborhoods of Chickasaw Gardens, Red Acres and Hedgemoor.

These three East Memphis neighborhoods created the demand for a “new downtown” along the Poplar corridor so that citizens of East Memphis could work and shop closer to home. To satisfy this desire, the city constructed Poplar Plaza in the late 1940s. Poplar Plaza was one of the first suburban shopping centers in America.

Annexation and White Flight

From the 1950s through 1970s, Memphis grew by leaps and bounds through annexation. Communities which had previously been on the outskirts of town, such as Frayser to the north and Whitehaven to the south, were now Memphis neighborhoods.

After desegregation and busing began in the 1960s, there was an influx of African American families, students and businesses into these “white” neighborhoods and their schools. This was promptly followed by a mass exodus of white families, students and businesses to suburbs and private schools. This trend became known as “white flight.”

White flight, an unfortunately common phenomenon in many, if not all, major American cities, refers to the pattern of white citizens relocating to suburbs as a response to racial integration. White citizens still held the majority of the wealth here in Memphis. And despite the Civil Rights Acts proclaiming forced racial segregation to now be unlawful, there was little stopping white citizens from willfully segregating themselves. Sadly, even today, there are very few neighborhoods or schools in Memphis which exhibit anything resembling actual racial integration.

By and large, white flight had a negative economic impact on neighborhoods. For a time in the 1960s, however, one section of South Memphis, now known as Soulsville, experienced a renaissance as a strong, middle-class African American neighborhood. Lemoyne-Owen College, a Historically Black College, and the success of world-renowned record label Stax Records fueled cultural and economic growth within the neighborhood. Sadly, due to a variety of factors, some racially motivated, Stax closed in the mid-1970s, and the neighborhood could not recover economically for many decades.

Downtown Left Behind

As the city continued to sprawl, cars became by far the most convenient means of transportation. The creation of Interstate 40 and the Interstate 240 loop created a situation in which wealthier families and businesses were no longer tied to the city center. White flight and the general appeal of the suburban lifestyle pushed Memphis’s population and revenue farther away. Downtown Memphis suffered. Over the course of the 1980s into the 21st century, Downtown became increasingly deserted.

21st Century

The 20th century was a busy one for Memphis. From 1960 onward, the city’s land mass had doubled. However, because of the rapid pace of white flight and suburbanization, Memphis’s population and tax base has hardly increased. As of 2019, the city has a both a general poverty rate and a child poverty rate more than double the national average. No major or instantaneous solution is on the horizon, but within the last decade there has been some newfound hope. Memphis has begun committing to increased development and revitalization efforts. Thus far, Crosstown and Downtown have been the primary neighborhoods benefiting from this effort, but hopefully they will not be the last.